An Intercepted Thing: The Epistolary Poem

“April is National Poetry Month. What better way to celebrate than with the Thursday Poets! Watch for us every Thursday as we offer poems and insights that help connect us to the community and beyond.”

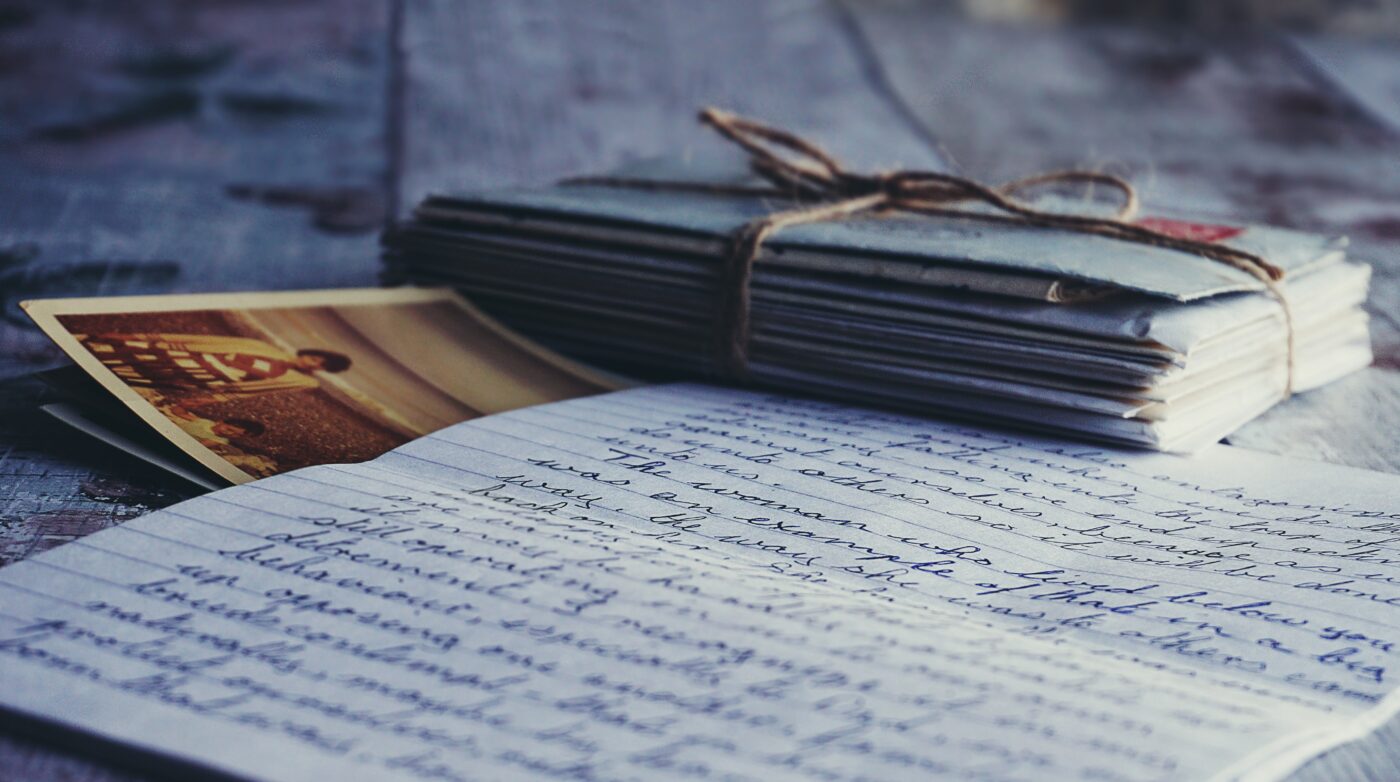

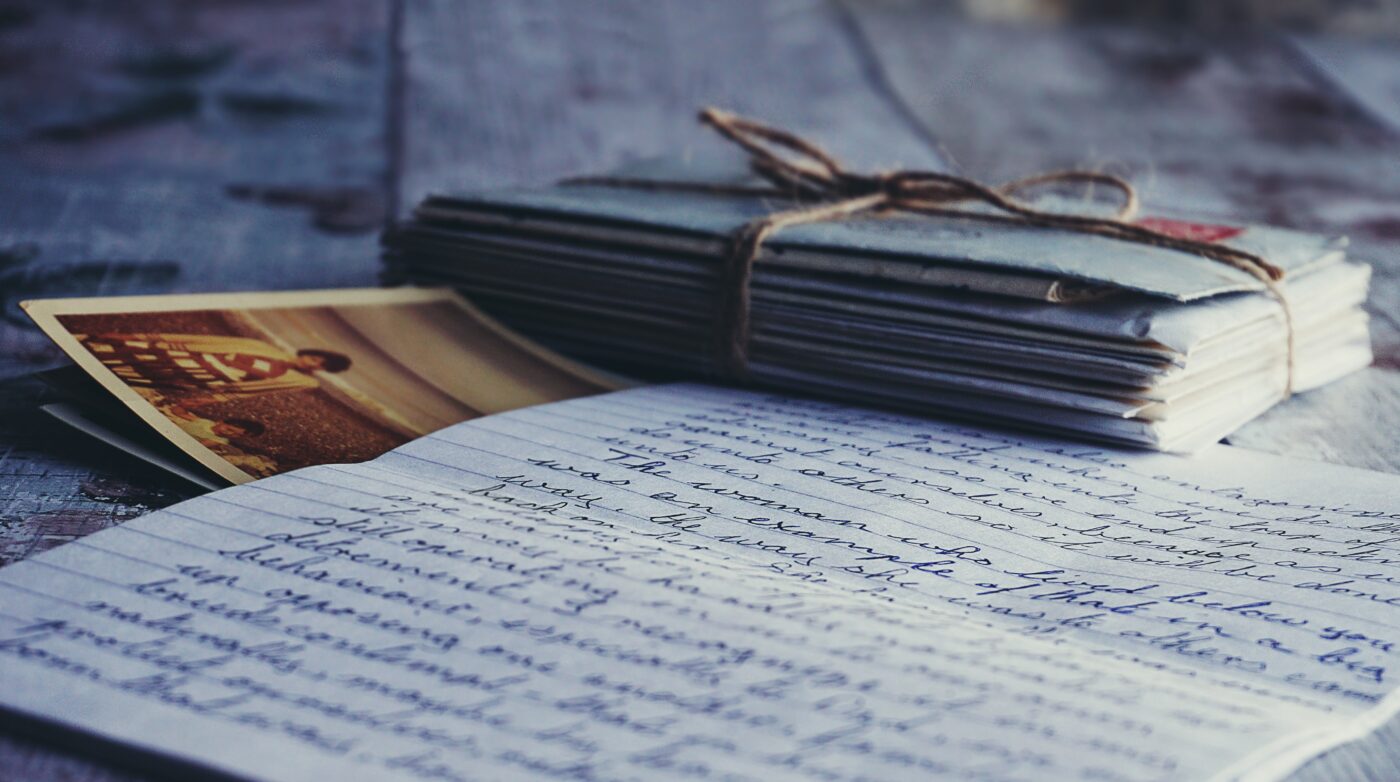

Lately, I’ve been drawn to epistolary poems—poems written as letters. To be even more

precise, as Paisley Rekdal says, a poem written as “a letter either intercepted or never sent.”

Perhaps I am nosy: the sender has a specific recipient in mind, has a message they want to

send—and somehow, it’s ended up in my hands. I love the idea of stepping into this urgent

place. I am now privy to this intimacy, this urgency.

I think this began as a mistrust of the “you” in poems: I’d find myself asking, who is this

other person? With an epistolary poem, the “you” is rarely universal, or unknown. From the

salutation alone, we know that this epistle, with all its concerns, has a purpose, a recipient.

Look at Wanda Coleman’s poem, “Dear Mama (4).” We immediately know who the “other”

is—the speaker’s “mama.” The opening question, “when did we become friends?”

encompasses aging, wisdom, intimacy, and love. Had Coleman written this poem as a

meditation, opening with (and my apologies to Wanda Coleman), “When did my mother and I become friends?,” I argue that the emotion would be lessened, perhaps sounding too

theoretical. We would lose the heartbreak and honest appeal to the mother in the following stanza:

and now

the thought stark and irrevocable

of being here without you

shakes me

With an epistolary poem, all the parts of the letter are important: the date, the

salutation, the signature. In this way, epistolary poetry is “found poetry.” For example, Tracy K. Smith, in her masterpiece, Wade in the Water, uses actual letters written by enslaved people to underscore their trauma and dignity, and to speak truth. As Smith says in her notes, “It became clear to me that the voices in questions should command all the space within my poem.” Listen to the appeal of Annie Davis in this letter to Abraham Lincoln:

Belair, Md. Aug 25 th 1864

Mr president It is my Desire to be free to go to see my people

on the eastern shore my mistress wont let me will you please

let me know if we are free and what I can do

Jessica Cuello’s recent book, Yours, Creature, is a collection of epistolary poems “written” by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley to both the monster she created in Frankenstein and to her

mother, the activist Mary Wollstonecraft, who died after giving birth to her daughter. The

correspondence speaks to loneliness and loss, but also the act of creation, with all its risks and

hubris. Closing her letters with “Your monstrous maker,” “Your loving servant,” “I kiss your imagined hand,” and “With a longing for your presence,” maintains the book’s emotional and

narrative arc.

This ancient form—the epistolary poem—has recently become a generative tool for my own poetry. It helps me to define the parameters of my work: to whom I am writing and why. The letter is my vessel, carrying on its lines urgency, intimacy, and honesty.