by Joey Phoenix

What happens when you have to start over after a major life change? Do you keep doing what you’ve been doing or do you let yourself become something brand new?

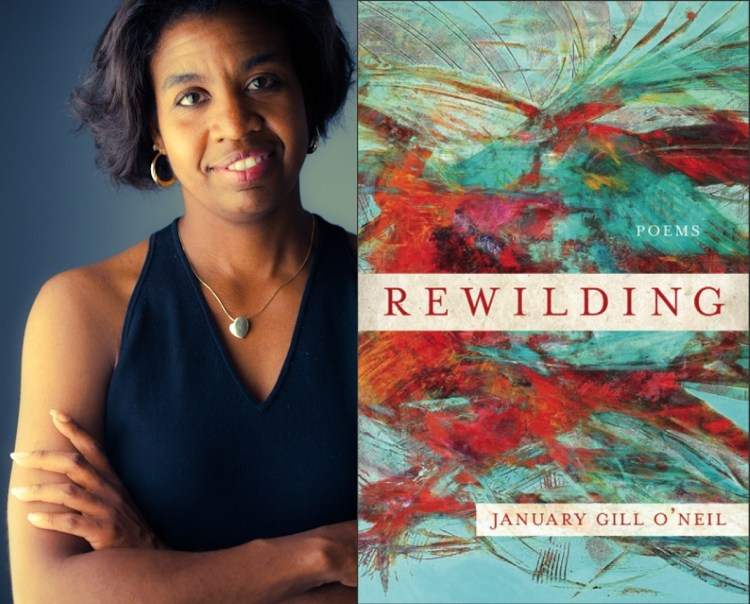

These are the questions January Gill O’Neil examines in her newest book Rewilding (Cavankerry Press, 2018).

Rewilding is a term for ecological, large-scale conservation where land that has been used for industrialism and cultivation – namely, for human use – is given back to the earth. When land is rewilded, it is returned to its feral, native state.

When a person goes through the process of rewilding, they let go of the life they ordinarily lead to embracing newness and unpredictability and a lack of control. This idea, spoken about by George Monbiot, author of Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life, is the inspiration and title for January Gill O’Neil’s new book of poetry.

A few weeks ago, January read “The Night I Wore the Purple Dress” for Color Me Beautiful, an Evening of Poetry at Streetside in Beverly, MA. It left the room breathless, the hush was a living thing. She spoke the words:

“the wispy, veiny, purplish light

that seeps through when making a wish –“

I felt that there was so much more to the story.

Having recently gone through my own rewilding – the end of an almost seven year relationship, the discovery of a new gender identity, and a subsequent move from the North Shore back into the city of Boston – I felt curious about what more poems of hers would uncover. The very idea of returning to a less restricted state made contact somewhere within my chest and I wanted to know more about what she meant.

Solidarity is healing and makes you feel less alone in your darkest moments. It shows you that if someone else made it through the wilderness, then maybe you can too.

So, when her new book of poetry was dropped on my desk, accompanied by the phrase “It will make a lot of sense to you.” I was already intrigued. I picked it up, pored over it, and didn’t put it down until I was finished.

Upheaval is something that comes to us in layers. At the beginning it’s not immediately apparent, but our intuition senses it first. In “Family Photo,” January describes it as the “root of something hidden,” and “the absence of light, just beyond frame.” You can almost taste it on the wind, and your subconscious is more attuned to it than your conscious mind can be.

The first segment of the book is dedicated to the devastating divorce she experienced and the immediate aftermath of that experience. It’s a swell from lovers meeting and growing together and breaking apart, to the details of a kitchen fire that left her afraid to enter the room for months afterwards, to a painting poem titled “A Star Caresses the Breast of a Negress” that ends in the line:

“Each star is a wish that never came true.”

In part two O’Neil begins to weave narratives about her relationship with her children, and what it means to be a single mother in a world that’s cruel to children of color, especially those from mixed families. In both “The Rookie” and “Hoodie” she discusses the casual racism that her son experiences in the presence of his teammates and in their neighborhood. In “Gracie” she describes how her interactions with her own father growing up impacts the way that she speaks to her daughter.

In “At Wolf Hollow” she writes the lines:

“To think wolves howl at the moon

is lunacy: their chorus to the night

is a survival song.”

To describe the alpha-wolf mentality of motherhood in dealings with family and children, and the feral nature of her words steps in again. I leaned into the words.

Over and over throughout this book she holds the readers close to her and shines a light over deep familial shadows. These sacred spaces she uncovers are ones so many single parents would want to hide away beyond closed doors. The elements of fear, joy, warmth, and coldness are treated equally as patchwork on a newly finished quilt.

Perhaps my favorite line in the book appears in the third part of the book in the poem “Unnaming the World” when, telling about a conversation with her daughter, she says

“When we fly we find our fire, she tells me. Also the blue part of a flame is the hottest and hurts the most. That’s why we’re attracted to flames.”

In Rewilding, O’Neil holds our hands as we walk through our memories, protecting us from their flames, but we feel the heat, nevertheless.

Click here to buy Rewilding from CavanKerry Press.

Joey Phoenix is a performance artist, pet photographer, and the Managing Editor of Creative North Shore. Follow them on Twitter @jphoenixmedia. If you have an idea for a story, feature, or pictures of adorable llamas, feel free to send them a message at joey@jphoenixmedia.com