Salem State’s Center for Creative and Performing Arts will open its 2022 fall season with ReWritten, Friday, September 16 at 7:30 pm in the Sophia Gordon Center at 356 Lafayette Street.

Get Tickets Here

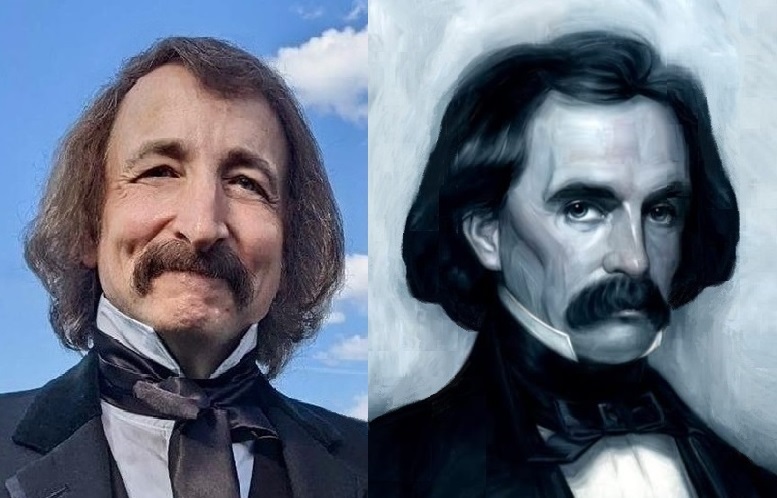

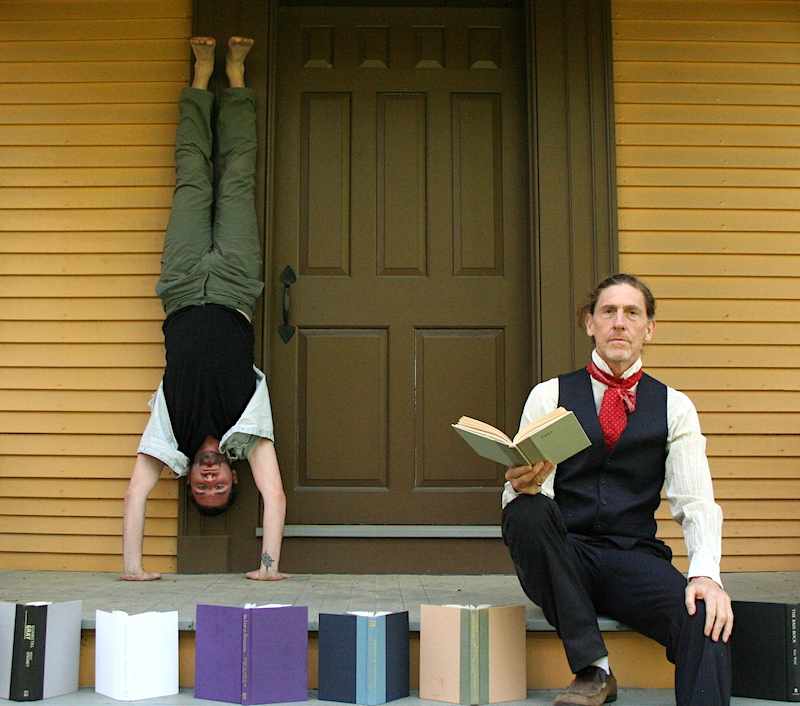

ReWritten is an immersive multi-disciplinary performance that explores the intimate relationship between authors Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville. Moving between their lives, work, and remaining letters, ReWritten reimagines an intergenerational queer love story that helped shape American literature. Through dance, live music, visual art, projection, and text this performance questions what happens when we say no to dreams when we want to say yes. Co-created and performed by Tom Truss (he/him/his) and Matthew Cumbie (he/him/his).

Joey Phoenix (they/them) met with the two creative minds behind the production to talk about the show, their process, and about the importance of LGBTQ+ representation in the performing arts.

Joey Phoenix: Hello to you both! I’m really excited to talk to you about this. My special interest is queer history and theatre, so I am astonished and delighted that this story is being told around the country through dance. So thank you for taking time to talk to me.

Tom Truss: You bet, and thank you for the opportunity. Joey.

Joey Phoenix: I would love to hear about who you both are and to hear a brief history of your creative process.

Matthew Cumbie This has been a whole adventure. Tom, do you want to start?

Tom Truss: Yeah [laughs]. I’ll start.

Matty and I have a similar background, we worked at the same place, which is called The Dance Exchange [originally Liz Lerman Dance Exchange]. It’s an intergenerational dance company that examines and dissects dissecting social justice and political issues through movement and words . It’s something that I’ve been doing basically, my whole life. I joined Liz’s [Lerman’s] company in 1989.

My background is music, theatre, and dance. I come from a time when being queer was a dangerous thing. I was part of Act Up and Queer Nation. But I felt more aligned to Queer Nation, whose mission was to wipe out heterosexism and homophobia in all its forms. It was less about shaming people and more about calling attention to things. And there was a lot to call attention to at that point. I lived in Washington D.C. as a radical queer during the Reagan administration, during the AIDS crisis.

But whether because of this or in spite of this, I just never fit into the traditional performance world. I never got cast in anything, because I either presented as gay or was too strange, and those words are oftentimes synonymous.

So I just started doing my own shit, and have done that my whole life in terms of creating work. And I became really good at this self-producing and making connections through art over the years.

Joey Phoenix: Awesome, Tom, thank you so much. All right. It’s your turn, Matty.

Matthew Cumbie: How do you follow that? Goodness. [He Laughs]

As Tommy mentioned, we have quite a bit of shared background in terms of what brings us to this work, what informs the work we do. I came into my art making in college, it’s when I really began digging into dance and how people consider dance and theatre and these different kinds of experiences.

What really drew me to [The Dance Exchange] was that it’s built on the belief that anybody and everybody can and should dance. It’s a part of our birthright. And while I was there, I was also drawn to the work because, like Tommy was mentioning, it’s an organization that helped me see the value of making art as a means to learn more about myself and the world around me.

I grew up reading a lot of books and I was really nerdy and loved researching. But growing up as a young queer kid in Texas, especially like someone who’s now about to be 40ish. It might not be surprising to learn that like learning about queer history as a kid was not really something that happened.

So it was during my early days with The Dance Exchange that I also started to become really curious about the lived experience that people like Tommy have had. And as a queer person wanting and needing to understand how I connect to my community, learning that history felt really important.

I started making work about queerness and queer history then. And it was really that trajectory that led me to meeting Tom Truss and to making this work.

Joey Phoenix: I’m very curious about why you chose this subject matter. It’s a matter of strong interest for us here on the North Shore. There are so many emerging queer histories around people like Sarah Orne Jewett and Emily Dickinson, but not as many people are talking about the Melville/Hawthorne connection. It’s a local legend – I work in Salem. And for us, it’s a very important thing, but not well known. So I want to know how you came across the information and why you thought it would be fun to pursue.

Tom Truss: I had just directed Frankenstein, at Siena College, for the anniversary of the publication. Mary Shelley’s language is so beautiful and heightened, and very dramatic, and I was like, I want to get my teeth into something that’s that juicy.

So I asked some friends of mine who are Wharton scholars and work with The Mount, Edith Wharton’s home out here in the Berkshires, to give me some short stories that I could turn into a theater dance piece. I read a bunch but nothing was inspiring me, and they kept supplying more and more stories, and then finally, Irene said: “You should look at the lettersHerman Melville wrote to Nathaniel Hawthorne, some people think that they had a thing.”

I was shocked. I don’t think I was in a car at the time but I distinctly remember feeling the need to pull over and take this in. So I read the letters.

Right after that Matty and my paths crossed while he was doing work at Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in the Berkshires. I invited him to come over and hang out on my deck When I first met him I knew instantly that I wanted to get to know him better and pitched the idea to him.

The whole process was very organic. It was obvious that he was smart, loved words and we had a common background and similar aesthetic. It just felt right.

Matthew Cumbie: I didn’t even know that these two men knew each other. I also remember you mentioning the age difference between Melville and Hawthorne at that time. Hawthorne was 15 years older than Melville. It was such a surprise.

I kept thinking what would that have done for little queer Matty growing up and seeing that relationship acknowledged in some way or reflected in the literature? How would that have changed my relationship to reading those stories as a kid?

Those two things really drove home for me the “yes, let’s do this” feeling. And I remember leaving that night I’d been like, is this going to happen? Because like you said, Tommy, we’d never worked together. We didn’t know if it was a good fit or not. And here we are years later still following the carrot that’s in front.

Tom Truss: And we quickly realized we complement each other really well in ways that I didn’t expect. A really good example of this is one time after one of the rehearsals Matt’s partner Tyler showed us an article in Poets and Writers Magazine about the artist Diane Samuels. She takes novels and poetry and micro transcribes them to create these extraordinary works of art. She did this with Moby Dick, wrote out the whole damn thing. It’s 47 feet long and 10 feet wide.

Her email address was at the end of the article, and I said “we should email her” which is something I would say but then either forget to do it, or just not do it at all. But then Matty pulls out his laptop and within two minutes composes a message asking if she’d be willing to have a conversation about collaborating with us.

She responded saying “yes” the next day.

Joey Phoenix: That’s incredible. I love this so much.

There have been a handful of different stagings of this production at this point. I’d love to hear about how the experience of this so far, and what have been some of your favorite moments?

Matthew Cumbie: We’ve been in process now for almost three years. And we have this incredible team of artists and scholars that we’re working with that really do stretch from Maine to Texas. We’ve got a projection designer (Roma Flowers), a fabulous set and lighting designer (Jeremy Winchester), a theater director (Rudy Ramirez) who’s helping us understand what we’re making and helping direct certain things. We’ve got Diane, the visual artist, and we’ve got a composer (Summer Kodama) that we’ve worked with occasionally now based out of Toronto. And we’re working with a queer literary scholar in Maine (Katherine Stubbs), a filmmaker in the Berkshires (Larry Burke), and a production manager in DC (Sarah Chapin).

So working with these incredible people who all bring so much to the project, and also working together for such a length of time, what we’re finding is that, there are many different chapters of the work that are starting to be created

And so as part of this project ReWritten, we have a whole series of workshops that we’ve led at universities and local libraries, including a course we co-taught at Colby College in Maine about performance making as an important research methodology.

We’ve got a screen dance that was filmed in the Writing Studio, where Melville wrote Moby Dick that was made by our projection designer. We’ve got this site specific exploration performance tour of Arrowhead. Another one of our collaborators in the Berkshires, Larry Burke is working on a documentary helping us to both archive the material and also think about what it’s been like to be a practicing artist making work during a pandemic.

We’re also working on a larger kind of staged production which is what we are bringing to Salem State University. We’re bringing an early draft of it because it’s not finished yet. But this is one of the ways that we are finishing it is through these opportunities to show what we have.

So there’s a lot of different things that have been made so far that we’re really excited to keep. There are some conference opportunities coming up. There’s some other possible engagements with performance venues and also other universities.

But for me what’s been really exciting about this work is the number of people that just find themselves drawn to this. It’s probably because it’s Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne that people are drawn like moths drawn to a flame. It’s something that continues to surprise me in terms of who feels connected to it, and how they can see themselves in what we’re doing.

Tom Truss: There’s also a shock value, right? Which is, How did I not know this?!? And and then there’s the paradigm shift, right? It’s a total prismatic change, in that I get to look at these authors and their work that has influenced so much of our literary canon from a different angle and through a different lens. And I would call that reinvigoration. People love learning new things like this and seeing old things in a new light.

Joey Phoenix: I love that so deeply. Does someone need to have knowledge of the work of these two men to approach the show?

Matthew Cumbie I don’t think so. One of the things that we both feel really committed to and that we continue to grapple with in how to navigate it is by incorporating as much of their text as possible. So there’s a lot of text that comes straight from either the letters or their actual written work, alongside texts that we’ve also developed as a creative team.

We feel committed to bringing that in both because the language they use is so beautiful, and it’s also another way to bring people into kind of the research that we’ve been doing to help illuminate that and help people understand how we got to XYZ. There are a lot of different entry points for people into this work, both through the dance movement, but also through the actual text we use. And that’s something that we’re trying to continue to suss out some, but I don’t think people have to know their works to know what’s going on.

Joey Phoenix: That makes sense.

As a last question I would like to touch on the representation element. Like you said, Matt, that, as a kid, if you had known that these two great men had been corresponding in this way, how would that have impacted your worldview? Why is queer representation in media so helpful?

Tom Truss: I grew up at a different time than both of you. There was no queer representation. And if there was , they were the serial killers in the movies. To have had this connection with Nathaniel Hawthorne, a person who my mother loved, and respected, as representation would’ve been something. My Mom had queer friends, and she loved and she respected them. There’s no question about it. She was in the arts.

But I think there would have been a sense of normalcy, as opposed to a sense of commodity around her friends. And the commodity was, “isn’t Richard funny,” or “Earl is so talented,” or Kate, “She’s a lesbian.”

But Hawthorne was normal. I don’t know why he was normal. He was normal because he lived 150 years ago? I don’t know. He was normal, because he wrote about normal things? It feels like there would have been a legitimization that could have happened. Had that been a part of my reading and understanding of Hawthorne, and for that matter Melville, who have been thought of and taught as straight, it would have made a difference!

Joey Phoenix: Yeah. Less othering. We have people like Byron and Walt Whitman and Oscar Wilde, who got ourselves in a bit of trouble from talking about it too much, but they were openly gay, and like something about the time period allowed for it. And then there was the movement of temperance, etc. In the 20s. It just became more complicated. I reviewed a play by Parker Goodreau actually put on as Salem State called The Thing They Love about hidden gay relationships during the era of Mae West.

Matthew Cumbie: Legitimacy certainly rings loud for me. And legibility also rings loud. I think I’ve been thinking about, like, Why did I read so much as a kid and why was I drawn to certain kinds of books and comics? a lot of it had to do with wanting to see myself reflected back to me not necessarily to make it legitimate, although I think certainly there is part of that, but also to make it legible. Like for me to actually recognize what I’m trying to say myself.

Queerness is such a gift because it helped me step away from all of these structures and trappings of heterosexuality that did not serve me, that allowed me to actually come to know myself a whole lot better, and way differently.

And if I had just known that sooner, if I could have found that for myself sooner, that’s the gift I would want to give to myself as a kid. I would have loved to just show myself what I could be like and how I could step away from the things that aren’t serving me.

I’ve never been able to articulate this in this way, so I really appreciate the opportunity. I think this is why for me, representation is so important. It’s both to give it that kind of outward feeling of: yes, this is legitimate, this is a way that we can celebrate life, and we can acknowledge it. And it’s also about making that way for people to find it for themselves.

Joey Phoenix: Thank you for the vulnerability in that answer. I think you spoke so much truth in that moment. I feel like when I read when I put these words out, people will relate to them. There is such a collective trauma of feeling alone…to be a queer youth and ask: “who else is like me? I am the only one like me.”

Tom Truss: For me it’s a sense of fantasy versus reality. In comic books it’s often a world that’s more fantastical and “better” than ours. A world where there are “freaks” or outsiders who get to step into and have their power, there is also a bigger and clearer sense of right and wrong.

I think seeing a normal representation of someone with my sexuality would have pulled me away from living in or retreating to fantasies, and put me in a place of reality, that, in fact, here are these men who are literary giants who are queers, bisexual, gay… something “different” like me would have been monumental. And even though they didn’t handle it well, or they weren’t able to handle it, or even define it, remember the word homosexual didn’t even exist when they were alive, there would be some sort of recognition that their sexuality wasn’t a fantasy. That they existed, that WE exist.

Matthew Cumbie Just to have that understanding that they existed is huge. It’s huge.

Tom Truss: I think about the wiping out of these histories a lot.

Joey Phoenix: The erasure. Yeah.

Tom Truss: This takes us back to ReWritten, our title. And, you know, it’s so interesting, that title. I don’t know who came up with it, I think it was you Matty – but it keeps being right. And after three years of developing this, it keeps being right.

There is a joy in being able to rewrite history. And it’s not that we’re rewriting it in a fantasy novel way, we’re rewriting it in an inclusive way. And I would say a more correct way. And we’re not the first to do this, my high school English teacher, and countless others, rewrote history by not bringing any of this up. And that’s still happening.

Joey Phoenix: Oh, that’s so true.

Matthew Cumbie: There’s a joy like you say, and I’d say there’s an importance in this too, and I want to recognize that, you know, as queer artists and as, as artists that experience marginalization in some form or fashion, otherness and belonging in some form or fashion, we’re not alone. I know that there’s lots of artists of color out there also doing incredibly important work to do this kind of revisioning, refashioning, and rewriting that I think is so desperately needed today.

Joey Phoenix: It’s like a new form of archeology in a way. It’s like, okay, like we’ve made major discoveries. We are reinterpreting history, according to actual facts. And it’s like Emily Dickinson’s house now has a queer tour.

Matthew Cumbie: It’s all being uncovered.

Joey Phoenix: Thank you both so much for your time and your energy. It’s so good to meet and talk to you both.

Matthew Cumbie Thank you. Have a lovely day.

Tom Truss: Thank you, so great to chat with you as well.

Salem State’s Center for Creative and Performing Arts will open its fall season with ReWritten, Friday, September 16 at 7:30 pm in the Sophia Gordon Center at 356 Lafayette Street.

Learn more about the project at: http://matthewcumbie.com/rewritten/.

What is Creative Collective?

Creative Collective is a group of economic development strategists, small business supporters, activation specialists, and believers in the importance of the creative workforce. We foster growth, sustainability, and scalability for small businesses, creative thinkers, organizations, entrepreneurs, and innovators.

Learn more and join Creative Collective at www.creativecollectivema.com/join