By Easton Mills

Live theatre has returned to Marblehead Little Theatre’s cozy Firehouse Black Box with Brian Friel’s Translations, directed by Trudi Olivetti and produced by Steve Black and Erin Pelikov.

Set in the fictional town of Baile Beag – no it’s not pronounced how it’s spelled – in the rolling greens of Donegal, a rural village in 19th century Ireland, Translations, by Brian Friel, grapples with language and communication in an effort to immortalize a notorious conflict of nations between warm Irish character and chilling British cultural imperialism.

It is a bittersweet homage to the evolution of the Irish “Gift of the Gab” as the plot moves from playful schoolroom to ideological battleground in Act 1. The pivotal clash which sets off the action occurs when two officers from the British Ordinance Survey arrive in Baille Beag for the purpose of anglicizing the local Irish place names.

In the scene, Captain Lancey (Bill Brauner) shouts condescendingly, as one often instinctively and wrongfully does when communicating across language lines, at the “uncivilized” rural Irish – many of whom speak multiple languages. The moment is comic by nature but, by necessity, doesn’t allow room to breathe, making the joke both claustrophobic and effective.

The act of renaming the Irish countryside is a dark example of Irish cultural erasure and discrimination as the rich and often lyrical language identifying Irish townships and crossroads is converted to bland English – a language which Hugh, portrayed sympathetically by Timothy Kenslea, states as an entity that “couldn’t really express us,” with “us” being the people of Baile Beag, and by inference, possibly the whole of rural Ireland.

Contextually, the British nation had been suppressing the usage of traditional Irish since the 14th century with The Statute of Kilkenny, which made it illegal for English colonists in Ireland to speak the Irish language and for the native Irish to speak their language when interacting with them

Young Owen, a former resident of Baille Beag and one of Hugh’s two sons portrayed energetically by Daniel A. Lefferts, is hired by the British as linguist and translator to the project. Lefferts’ enthusiasm as Owen creatively (read: misleadingly) translates from one language to another is pitchy and overbright at points, but comes through beautifully during Act 2 when describing the obscure and potentially obsolete nomenclature of a particular Irish crossroads.

Owen’s father Hugh himself is a clash of civilizations as the oft drunken elderly Irish hedge schoolmaster is proficient in Greek and Latin as well as English. His love of the classics plants him firmly in the romantic notions of the past as the present slips slowly into the era of modern colonialism.

Hugh’s primary scene partner and emotional scratching post is a tramp named Jimmy Jack Cassie (David Foye) obsessed with Homer and his hero Ulysses. The two of them enact a minor tragicomedy within the larger scope of the production that left this reviewer feeling impatient and anxious rather than sympathetic, but perhaps this was the point.

There were three other pairings within the production worth remarking on, although one side of each was markedly stronger in each duo. These were Manus (Malachi Rosen) and the ever quiet Sarah (Victoria Berube), Máire (Hannah Noel Schuurman) and Lieutenant Yolland (Josh Whiting), and Bridget (Caroline Alix) and Doalty (Juice Wacker).

The play begins with Manus, Hugh’s younger son whose nascent teaching ability aims to surpass that of his father, encouraging the mostly mute Sarah to speak her name in English. Manus, also disabled from a childhood injury, has a quiet stage strength that matches and balances the exuberance of the entire ensemble – which allows for the rash choices he makes later in the production to have striking and timely emphasis.

Sarah, however, falls into herself in a way that feels somewhat misguided. The character feels like a story yet undeveloped, and this reviewer wished that more had been done to draw that out beyond a mere plot device.

Truly representative depictions of speech impediments and vocal disabilities in theatre are uncommon, but poignant when present. In an art where language and vocal tones are trained and prioritized, viewing a mostly non-speaking role on stage is an opportunity for both a discussion of disability erasure and a creative turnabout from linguistic presence to physical capacity.

Yet, even so, in a play this rich the acknowledgment of a secondary barrier experienced by Sarah’s character, not just in language itself but in the ability to speak at all, was not missed or lost in the shuffle.

Next, in the duo of Máire and Lieutenant Yolland, Máire shines brightly. The audience watched as the feeling of being trapped in a place too small for a woman of her longing and ambition grated visibly. Each moment of hurt, joy, frustration, hope, and grief danced artfully across her face throughout the course of the production.

An overwrought milkmaid who dreams of learning English and going to America, Máire is drawn in by the young soldier, and while they cannot understand each other at all – this scene where this plays out has historically been one of the most famous moments of the production – the sweetness of their hope and yearning for connection is plainly evident.

Perhaps Yolland’s strongest moment, however, is in Act 2 where he, in an increasingly drunken exchange with Owen, expresses a fervent desire to learn Irish and stay in Baile Beag. He dreams of belonging to this place, and fears that he may never be able to decode the language sufficiently to ever be accepted by the community.

Lastly, the interactions between Bridget and Doalty and these two’s gossipy interruptions to the hedge school room were important for exposition but failed to rise far above stereotypes. Doalty is believable as a brash, British-hating Irishman of principle ready to sharpen his teeth at the expense of British soldiers, and Bridget’s energetic descriptions of off-stage happenings provide texture and move the plot forward well enough.

The staging of the production was rustic and mostly unobtrusive. However, a nod to the lighting work must be mentioned, particularly during the most difficult moments in Act 3, when the set was bathed in a haunting glow from activity happening in the British camp. The moment was so drawn out and carefully placed that it affected the temperature in the room.

Overall, Translations is a thought-provoking production worth seeing. It is a dark and textured performance that artfully handles this fraught period in Ireland’s history, and serves as a perfect backdrop for drinking whisky and baking Irish soda bread this March.

And lucky for the readers who wish to see it, there are a dozen or so tickets remaining for tomorrow’s (March 12th’s) showing. Tickets are available at https://www.mltlive.com/2021/10/translations.

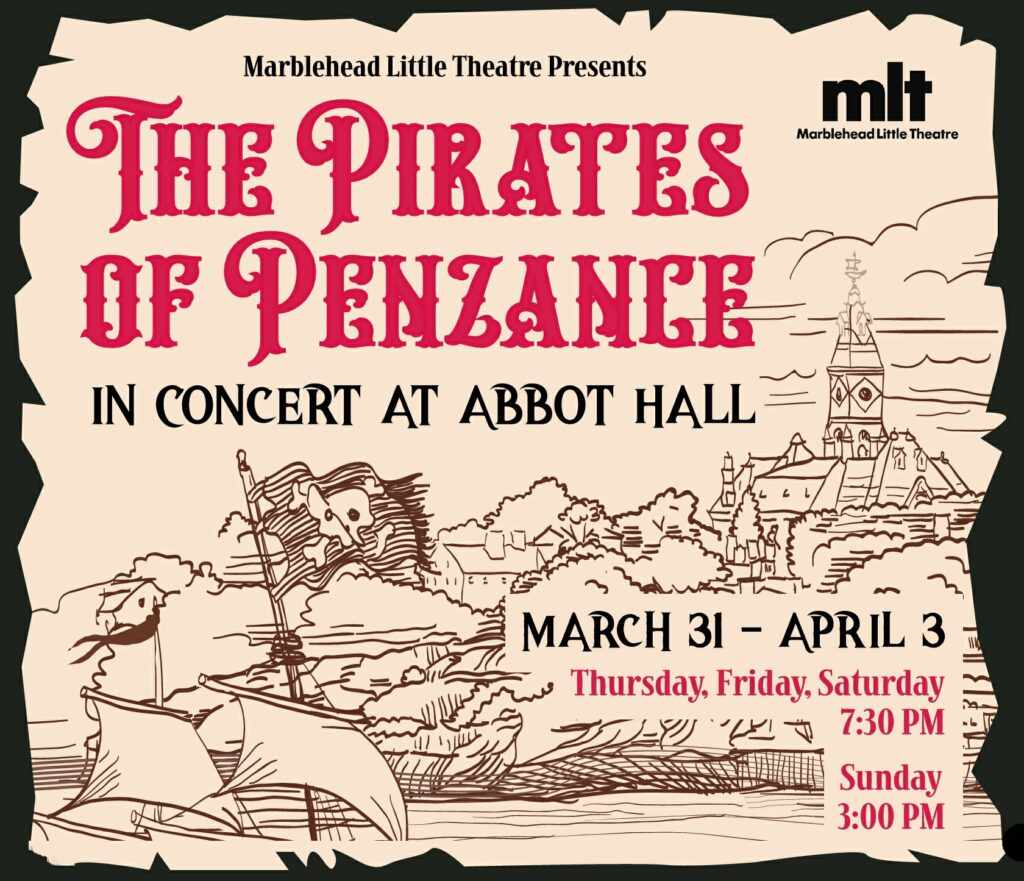

Up next at Marblehead Little Theatre is Pirates of Penzance, which will run from March 31, 2022 through April 3, 2022 at Abbot Hall.

Easton Mills is a contemporary theatre critic fascinated by language, rhetoric, and weird puns nobody else notices. He is a dog dad to Marshall and an aspiring birder. Follow him on Twitter @EastonMWrites

What is Creative Collective?

Creative Collective is a group of economic development strategists, small business supporters, activation specialists, and believers in the importance of the creative workforce. We foster growth, sustainability, and scalability for small businesses, creative thinkers, organizations, entrepreneurs, and innovators.

Learn more and join Creative Collective at www.creativecollectivema.com/join