You can explore the accompanying presentation deck here. Recording can be found here.

I really, really appreciate it, and I am really honored to be the executive director of the New England Foundation for the Arts. We’ll hit on some of that. I’ll just say New England Foundation for the Arts – NEFA. We’re in the midst of the strategic plan, so it just feels like we’re so close to a new vision. I’m in a bit of a bind because they haven’t approved the new thoughts, so I can’t really be public about it, but we’ll sneak some ideas in there and see what else might be useful.

Our topic today is “In Culture We Trust: Thrive in 25 Tourism, Arts, Culture and the Future of Resilience.” As I was saying to Nancy, I don’t know if your other speakers have been so difficult when she asks for a topic and you’re like, “Oh, I can’t give it to you” the day before the speech is still being written. I think there’s some relevance there in this speech, but it sounds like you’ve been talking about trends, you’ve been talking about arts and culture. So hopefully I can animate and amplify things that you’ve already discussed.

When I hear my bio, I know it makes my father proud, makes me cringe. Because while all of that is true, it doesn’t illustrate some of the hardships and the opportunities and what it has taken over this time to really be that individual. And then, even though my daddy is proud, somehow it doesn’t make space for him and my mother and the people who are definitely responsible for my being. So I always reintroduce myself this way:

Harold Rosa. bare skin.

When he is young.

His youth is of no concern.

There is melon in the middle of the fridge.

A Father’s back to charter… barefoot.

The lights always come on on cue.

Water basins are full warm.

Heat to welcome winter.

Air to combat the sun.

Song on Sunday morning.

Blues in the midday light… Hip-hop comes later, but we know it’s coming.

A grandmother at the top of the hill

Aunt and Uncle too

Hell to be raised, spirit to be free.

Vacations and vacant lots.

A boy at school.

Curved ball on Saturday morning

Sun Tea and summers.

A dog tied to a tree,

a neighbor’s room to roam.

A sugar cookie from Pats.

Clean clothes in the basket.

Weed unless we’re talking about marijuana. In the can.

St. Augustine on the back.

An Easter speech, a haircut, a fishing ride, A little brother, a niece, nephews, nieces.

A nephew. Street lights, curfews.

Beds for dreaming… and bare skin.

I introduce myself in that way one, because I’m a poet and an artist, and it seems more relevant. It makes space for the people who are really, really important to my opinion and my way of life. And it just allows me not only to be a creator but to honor them. And in this picture, you’ll see the neighborhood that I refer to my mother and my little brother. I’m actually the 7th of eight, but I only had one little brother, so I just claim one sibling. Like that’s the only one that really mattered – I got to be older than him. So that is a picture of us.

This poem takes its inspiration and even its form from Nikki Giovanni, our newly departed ancestor. There are a lot of things that I’m grateful for in terms of how she’s influenced my life and my career and let me know that Thug life is even relevant to college professors. We can also connect to that. She died recently, and I’m glad I got to meet her in my time in Boston and had already written this poem about my childhood. She writes a poem “Nikki-Rosa” that talks about her childhood.

I think it’s also important to understand – while I did say yes, and I said yes quickly, probably not even understanding what I was going to be asked to talk about, but it was like, okay, it’s in my region. She said nice things about my formal speech. You don’t really have to take the real here. Not a lot. So it convinced me. Yeah, I’ll come.

But then, when really understanding the industries and the connections I would be talking about, it’s like, well, what gives it relevance? And I have to tell you, I’m a proud child of Dallas, Texas. And when I think about the word tourism, unfortunately, it has no relevance or space or use in a neighborhood that raised me. And so I’ve been thinking about that. I try to talk about it in such a way that I only acknowledges these people.

The neighborhood that I come from in Dallas, Texas, is technically a black settlement. It was built in the 1970s over undeveloped land in Dallas, Texas. And if you think about this time, it was a time in which there were some existing houses that were built in our neighborhood in the 50s. But by when we get to the 70s, Dallas, like many urban cities, had experienced something called white flight. The white people, for whatever reason, were leaving the urban cores and moving to the suburbs.

And so for a city like Dallas to even think about how it might survive and thrive, it now had to pay attention to many of its citizens that it had historically ignored in terms of housing segregation. But when white populations in large droves chose the suburbs, now this focus was on young African American families that were looking for opportunities to raise their families.

My parents are now ancestors. I’m helping care for our family home, and I’m digging deep into this history, and it’s fascinating to me. Because my parents moved into that house – 6822 Balalaika – in ’72 and I was born in ’82. So this is ten years of knowledge, and now I’m just catching up to it. And it’s fascinating because what I’m learning about this black settlement called Singing Hills in the area that we live, literally is called Hidden Valley because at one point you had to cross the lazy river to get to now where my neighborhood is.

I’m learning that the city, to attract these young African American homeowners – my mother was 22, and my father was 28 when they moved into this house, and they had young children – they got one of the best architects in the city to build late model, mid-century modern homes. And so this is really fascinating to me as I understand this community because I know this community as an all-black community, people who really were working class, if you want to say that. Or blue collar. Sometimes no collar. Who does all of these things.

It still is a politically charged and civically engaged neighborhood, and we turn out the largest numbers in voting. I know this because my aunt and uncle also moved in this community, actually ahead of my family. So it’s, 7022 Balalaika was a model house in ’71. My aunt and uncle and grandmother moved there. They allowed my mother and father to live there with whatever young children they had while 6822 Balalaika was being built.

I know a lot about our civic engagement because my aunt has been the precinct chair as long as I’ve been alive. And so she organizes everyone to come out and vote. There’s a lot of pride in Singing Hills turning out record-breaking numbers no matter what the election is.

So when I think about this, what it means to live in a black settlement with civically engaged people – and still, if I was talking to them today about this keynote, the concept of tourism may not resonate. They may talk about things like, “Oh, yeah, when we went to East Texas to visit our grandmother,” right? Or “We went to Fairfield because baby girl, you know, had a volleyball game.” And now we’ve decided to play some of the neighboring towns and cities. And lucky habit is that a team from Oak Cliff, Texas, where Singing Hills resides, is now state champions are going against the state of Texas in a football game – we go to Austin, but they wouldn’t describe it as cultural tourism.

So I understand cultural resilience through this type of upbringing, but still, this talk has to make space for people who may not use the language that we use in this room to really understand what is it that we’re actually getting to. And I say why do my people not understand tourism? They’re vibrant, they are active, they’re engaged. It’s because they would never see themselves in the transactional nature that tourism almost implies. We don’t go to spaces where we can’t find a sense of belonging and home, and tourism for us is if we have to go to a government agency, drop some papers off and leave. Right? But it’s not the kind of places where we find our residence and homes.

So I ask us to hold that as we think about who knows and uses some of the terms. But again, I wouldn’t be Harold Steward, and I wouldn’t be the person who thinks in these ways if I didn’t just acknowledge and make space for the ways in which my cultural way of being thinks about tourism.

The bio and the work may indicate that not only am I arts and cultural practitioner, but I have this particular approach to arts and culture that I like that seems more relevant for me, and I call it “arts as applied social science.” Arts as applied social science concerns itself with the psychological well-being and social welfare of individuals, communities and society.

Many of you in the room may or may not identify in the arts and culture space and sectors. So this is an invitation – actually, there’s nothing precious about this definition. Use this. But also insert yourself in your work in there. Maybe tourism as applied social science concerns itself with the psychological well-being and social welfare of individuals, communities. As hospitality as applied social science does it also have this list of concerns? Right, the food industry? And by and large, I hope that our government employees here who work in government could say we work in a type of municipal spaces that concerning them as applied social science concerns itself with these individuals and these issues.

So hopefully, just by adopting or really inserting yourself into the definition, we can find home together in this talk. I am a college professor. And every keynote that’s not in the classroom, I say don’t go up there and be a college professor. They ask you to be a college professor, and every time I fail, right. So part of this will be about terms and definitions, just to make sure we even the playing field, we all have the same sense of understanding what may be meant. And then we’ll do a little activity where we think about impact and opportunity.

Whether it’s a trend or not, it may need to be a trend today. But just bear with the college professor while he goes through a couple of key terms and definitions. We won’t have to read them all because you’re the smartest people north of Boston. Psychological well-being refers to the state of feeling good and functioning effectively in various areas of our life, right? Let’s hold that definition.

It encompasses several dimensions, including emotional well-being, psychological functioning, self-acceptance, purpose in life. And you’re going to get these slides, so you can look at the terms here. Positive relationships and autonomy, identity reclamation. What I work with – Nancy kind of gave the description of how oppressed people reclaim agency over themselves through culture production. That’s autonomy. Right? So psychological well-being does have this interesting connection with autonomy.

Social welfare, right. Social welfare refers to this system and set of programs and services designated to promote the well-being of individuals and communities, particularly those who are vulnerable. Right. Social welfare systems vary significantly between counties reflecting different cultural values, economic conditions and political priorities.

When we think of social systems, we think of welfare systems, and that’s great. There’s these everyday un-institutionalized social welfare systems that we should also be concerned about. And if you are an institution in this room, you should see yourself at the intersection of social welfare and social systems, no matter what it is you do.

Social scientists we know, right, are a group of academic disciplines where we study society and social relationships. Some of them neatly listed here in psychology, sociology, anthropology, economics, and we’ll come back to that. Political science and geography, history too, continue communication studies. Right. We just heard wonderful examples of marketing, digital tools and all of that in communication studies and social work.

Then, because I have to understand it is not a part of my upbringing, what is tourism? Right. And tourism is the activity of traveling to and staying in places outside of one’s usual environment for leisure business or other pleasures is one definition.

Look at the types of tourism: leisure tourism, business tourism, cultural tourism, eco-tourism and adventure tourism. Right. So definitely we did this a lot growing up. But again, the term tourism was not what we were seeking. One, because we were seeking authentic relationships. We were being opportunistic on these adventures and seeking a way to find home. Never was anything transactional. Transactional ways of being was given the causatory to pay the water bill – you stay in the car, I pay the bill, I’m only going to be in there one to two minutes, don’t get in trouble, right?

Impact of tourism, right. And I’m sure you know this. You’ve probably been talking a lot about it today. There’s an economic impact, definitely the cultural impact that I think we’re here to uplift, and the environmental impact.

And before we go to how to integrate this into arts and culture, there’s some things. The other piece that I would read comes from Toni Morrison, where Toni Morrison really talks about, I think, not only the threat and opportunities in economic industries, but also a strategic use of arts and culture.

In 1975, Toni Morrison is called to be maybe a keynote speaker at Portland State University. And it is Portland State acknowledging not only the anniversary of its being, but they’ve also pulled together their black studies program. If you are a student of history and especially development of black studies program, you know, they only started in the 70s as a part of the black liberation movements.

So in ’75, Portland State University has already secured Toni Morrison to be in this, what feels like a closed room environment, and to give a keynote, which she calls “A Humanistic View” to the theme, the American Dream. Right. In 1975. In the speech, Toni Morrison discussed the interconnectedness of economics industries and the role of artists in society. Morrison emphasizes that artists can profoundly influence culture and contribute to the economy by challenging social norms and provoking thought through their work. She highlights how the creative industries can drive economic growth while also addressing the importance of community and shared experiences. Morrison advocates for the recognition of artists not just as entertainers but as vital contributors to societal progress and economic vitality.

The speech calls for an understanding of the value of artistic contributions and fostering an environment that supports the creative economy. A couple of excerpts from that speech that have been really relevant to me as I seek to understand more not only my work in this world, but my role as a black individual and an artist – Morrison, who I try to model my speech giving after, starts the speech like this:

“Right after pitch and rice, but before tar and turpentine, there’s the listed human beings. The rice is measured by pounds and the tar and turpentine is measured by the barrel weight. Now, there’s no way for the book entitled ‘The Historical Statistics of the United States from Colonial Times to 1957’ to measure by pound or tonnage or barrel weight, the human beings. They only use head counts.”

She says the book that she’s referring to, the historical statistics of the United States full of fascinating information. And in about three or four pages, more than it is attributed to rice, they talk about the human beings – those slave exports that came to the United States from 1619 to 1716. She says, “Put note five is very civilized. It says, ‘number of Negroes shipped.’ Not those who actually arrive. There was a difference, apparently between the numbers shipped and the number that actually arrived.”

Morrison says, “The mind gallops over to the first unanswered question. How many? How many were shipped and how many did not arrive?” She said, “You can’t think about that in the same ways that you think of rice and turpentine when you’re talking about imports and exports.”

Morrison asked the question, was there a 17 year old girl there with this tree-shaped scar on her knee. What was her name? Could you please tell me, what was her name? Then she asserts, historical statistics are not required, certainly not expected to provide this type of information.

It’s done it’s job and it’s done it well. Now, that’s simply what economic industries like. If we go back and think about tourism, and if we limit tourism only to its economic impact, we miss so much. We act like these inspectors that are looking at pounds and tonnage and things like that. We never know the name of a 17-year-old girl. We never know some of the features of her being, so it’s quite dangerous. Although it is important to think about tourism essentially as an economic driver, good news is, all things relational and other impact – that’s where the artists come in.

That’s where culture can help amplify. And if you’re stuck, we can help you. Don’t just be stuck in the numbers and marketing and the real transactional nature of being, because there are cultural people like me seeking a different way of belonging in this industry called tourism. Arts and culture can make change happen.

And it’s interesting because I promised myself that definitely for the next four years, I’m going to maintain a sense of peace and siblings of life, joy that I found over the last couple of months. So no administration, no social conditions can really disrupt that. But I have to say, when you hear America 250, some of us have a visceral reaction to it.

But we understand the intent and the beauty and all of those things. This is no disrespect to those who are charged with helping us think about a very charged history. It should be acknowledged. I wonder how much of it should be commemorated, right? And I know the people in this room, as we’re thinking about how to address it with a degree of honesty – I’m a theater person, so of course I love a reenactor, right?

But today it was funny just hearing some of our colleagues really think about some of the work and create those invitations. I knew this slide was in the presentation. I thought, what would it be to think about America 250 through this lens and this continuum impact? Because that really is an open invitation. And how can arts and culture really help? Not only animate some of its truths, but again, if we just think about America 250 and all we need and hope to do, this continuum of impact, let us be one of our last activities to work together through this.

Arts and culture can make change happen through the continual impact of America 250. Knowledge – what people know, what do we want them to be aware of and understand? How can artists and cultural workers and cultural institutions and arts institutions influence America 250? Be knowledge bearers, right? Discourse – how people communicate. The dialogue and the media and all of those things that are created. Seek out artists for those opportunities as well as you think about whether it’s 250 or other things. We are real good strategists in the discourse, no matter what the topic is that one might want to create.

The attitudes – how people think and feel. I tell you, I’m already charged, and I did a lot of good Kumbaya work this morning because I was working on other things in response to the administration and actions this week, so it’s good to center oneself. But then you have to recharge. There’ll be people when you say America 250 like me – we think, and we still. And if you’re going to be honest about it, and if Massachusetts is going to claim to be the birthplace of the experiment called America, understand many people will be thinking and feeling, and how artists, cultural workers could be instrumental in that thinking and feeling from a values place, from a place of motivation, and from a place of vision.

Capacity to know and believe – you think a lot about social capital and leadership. Who really is leading the charge? And telling these stories? And amplifying these narratives and really being engaged? We were talking at my table – it’s important for me to say when we think about collaborations with artists and culture workers, I should have to say it, but I will make sure you pay them. So as you’re budgeting a little more, especially when we’re thinking about capacity building strategies and all of those things – and social capital is good, it just don’t pay the bills. Make sure that there’s some money in there and some identifiable artistic leaders – not me because Nancy took my last free gig. There are other people out there.

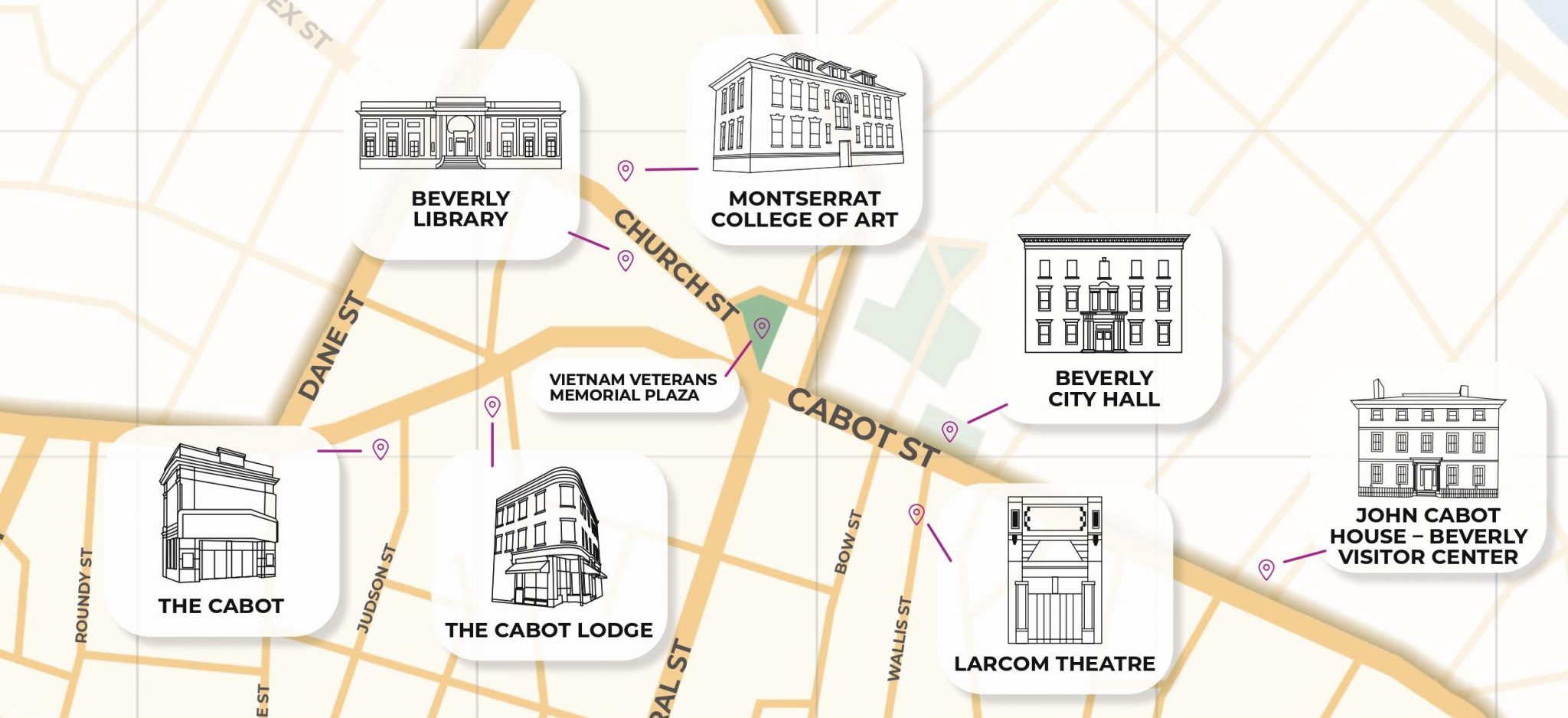

And I would say NEFA has a resource full of artists all throughout this region called Creative Ground that you can go to now. And if you want to search who’s in my neighborhood – is it a dancer? Is it native folks? All of that? We have a free tool called Creative Ground that will help you think about where is artist leadership and who can be engaged.

Then actions – not only should we think about acknowledgment – I’m still trying to get a right relationship with that word commemoration as it relates to America 250, but I can hold on to acknowledgment. What can we participate in and what can be mobilized? Not only from a marketing perspective – come to the event, come see it – but what else could happen because we’re living, breathing these histories still live with us, especially in this land.

And then finally, this is a tool that we’re using for NEFA’s strategic plan, and we’re reintroducing ourselves as a social impact organization. I tend to say, I don’t care what we do – I actually do – but what we have to do is make sure that the work that we’re doing is changing conditions, that is making a change that lasts. We’re looking at systems where physical conditions access and equity – and again on the theme of America 250, I will tell you, an advocate is not enough if there’s not something along this continuum to think about the conditions today in which everything Massachusetts and other individuals in this society have contributed to the development of this nation. What conditions must be sustained? Must we grow? Must change?

This is how artists can work with you. And no matter what the industry is, we’re going to hold truth to the Province of this nation, the inclusion of this nation. And finally, I’ll say again, since we’re there, and I love to be here with you in beautiful struggle and artistic possibilities – we also have to factor in America 250 can be acknowledged during this administration. How do we make space? Hold all of those truths and conditions and still show the beauty that each and every one of you offer and whatever influential organization or business that you may have?

I think that is our charge. And when we talk about trends, the great thing is we got a little bit of time – we ain’t got a lot of time. So when you think about where do artists show up in my work right now, in relationship and belonging and all of that, start examining that right now. Where might there be capacity and true collaboration right now? Am I in deep relationship with arts and cultural workers or am I at a transactional relationship? Well, our logo could use some – you can put your art there and put it like price on it, and we’ll sell it, right?

The call is to be in deep relationship. We need the transactions – yeah, love to sell, love to be utilizing those other ways, but again, transaction all along, and I’m not saying you do that, I’m saying don’t do that. Seek out ways to be in deep relationship and most brilliant minds this society has ever cultivated. It’s been hardest, most strategic minds of this society has ever created have been artists. Sometimes we’re not always acknowledged for those ways of being.

And you think about it, I’ve been traveling New England for almost two years now in this role, and I had to get out of Boston because Boston tells a very limited story of New England, doesn’t tell the north, the Boston story. And what I’m surprised about and when I moved by is that New England has a lot embedded in its history. But to think about New England and the industries that were once here and left – what happened after that, when mill towns or towns that were creating stone or whatever the driving industry, what farmland? When those industries left, artists remain. They occupied those barns. I live in western Massachusetts on a 120-acre farm managed and owned by Double Edge Theatre.

They went into those old mill towns and those abandoned warehouse and buildings, and they saw possibilities. Some of them – the buildings were dilapidated, the conditions were unlivable. But still, artists have never left the communities they call home. So we’re indebted to artists because they stayed long enough, like many of you, for industry to return to be renewed and for people to come back.

So I don’t know if I talked about trends, but I definitely uplifted some thoughts and ideas and some long games. I’m gonna end there because Nancy really wants to end on time. We’re only five minutes over. Thank you.