Power and Perspective: Early Photography in China On view September 24, 2022 through April 2, 2023

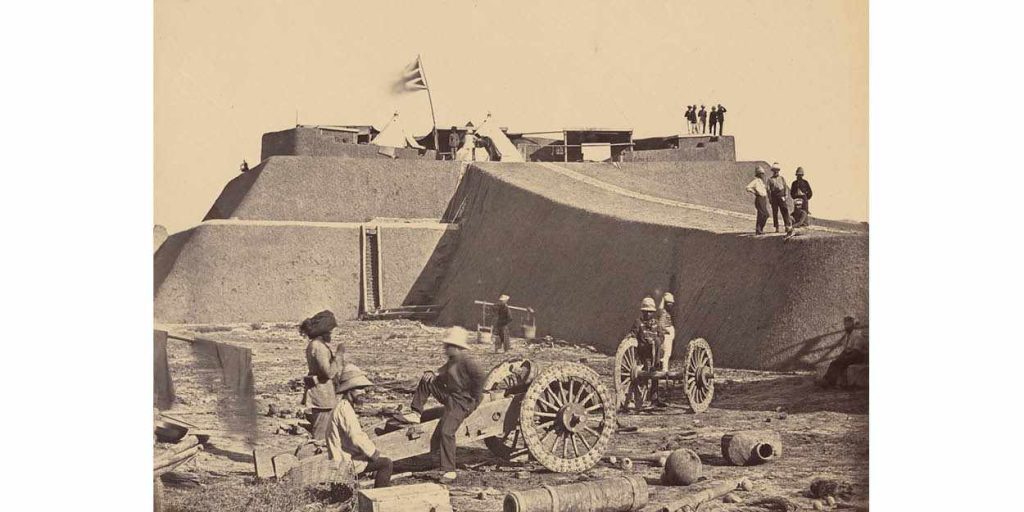

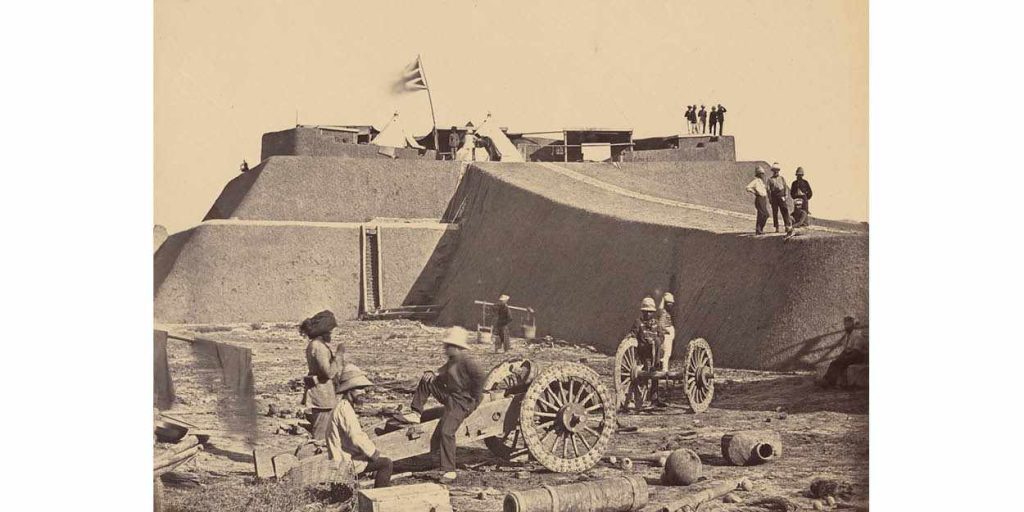

The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) presents Power and Perspective: Early Photography in China, a new exhibition that explores how the camera transformed perceptions of 19th-century China. Photography’s development as a new art form and technology in the 19th century coincided with profound changes in the way China engaged with the world. Through a rich account of exchanges between photographers, artists, patrons and sitters in Chinese treaty ports, Power and Perspective provides a vital and timely reassessment of photography’s colonial legacy through more than 130 extraordinarily rare photographs accompanied by paintings, decorative arts, and prints. The exhibition, on view at PEM from September 24, 2022 through April 2, 2023, concludes with work from a collaboration with emerging photographers in China, who interrogated the historic photographs in the exhibition and responded with works that offer their personal insights into China today.

“The premise of Power and Perspective is that making a photograph is a social process. A photograph demands the engagement of many people—some willing, some less so—whose presence always rests outside the frame, and yet they make the event of photography possible,” said Stephanie Hueon Tung, PEM’s Byrne Family Curator of Photography and exhibition co-curator. “Photography has never been a neutral technology of documentation; who and what gets captured and the stories that these photographs tell is a function of power.”

While the legacies of photography and imperialism are without a doubt intertwined, this exhibition asks us to consider the relationship between images and power in order to understand how photographs have shaped our view of the past. No sooner had Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre published the details of his 1839 invention than photographers set out to capture the far reaches of the colonial empire. Following in the wake of war and colonial expansion, the first photographers in China created extraordinary images that often reinforced Western interests and claims of authority. Chinese artists and patrons also adopted the medium, expanding the practice of photography to serve their own creative purposes.

Artistic Exchange

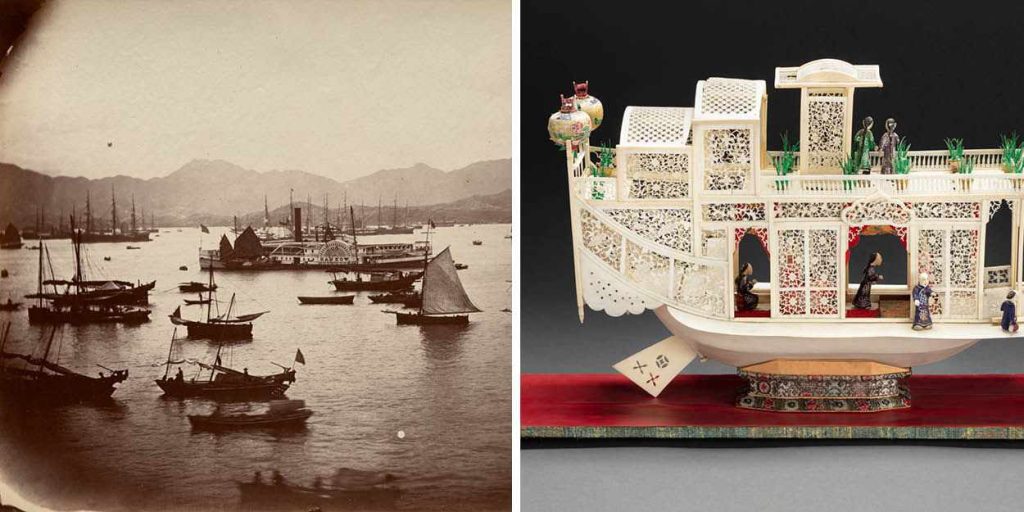

In November 1844, the Cantonese oil painter known to foreigners as Lamqua, visited the foreign settlement in Guangzhou expressly to see a new wonder: the daguerreotype camera brought to China by French customs official Jules Itier. Lamqua requested a demonstration and Itier obliged, making a daguerreotype portrait of the painter and sharing it with him. One week later, Lamqua returned with a gift for Itier: a miniature self-portrait on ivory, which Lamqua had carefully painted after his photographic likeness. “Lamqua and Itier’s moment of artistic exchange marks the introduction of photography in China and demonstrates how Chinese artists adopted and adapted this new form of art and technology into a vibrant existing practice,” said Karina H. Corrigan, exhibition co-curator and PEM’s Associate Director – Collections, The H. A. Crosby Forbes Curator of Asian Export Art.

Photography and the Treaty Ports

Following the Opium Wars, foreigners were granted unprecedented rights to live and trade in designated treaty ports like Shanghai and Guangzhou. These cities, which were under Chinese control but administered by foreign-led municipal councils, were shaped architecturally, culturally, and socially by the arrival of foreigners. These regions became economic hubs and fertile ground for new ideas and technologies, including the establishment of China’s first photography studios.

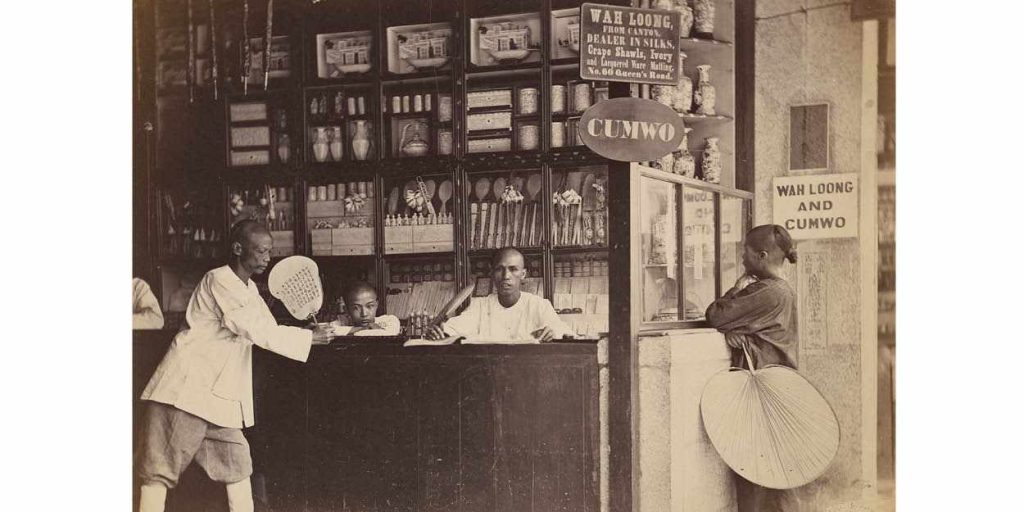

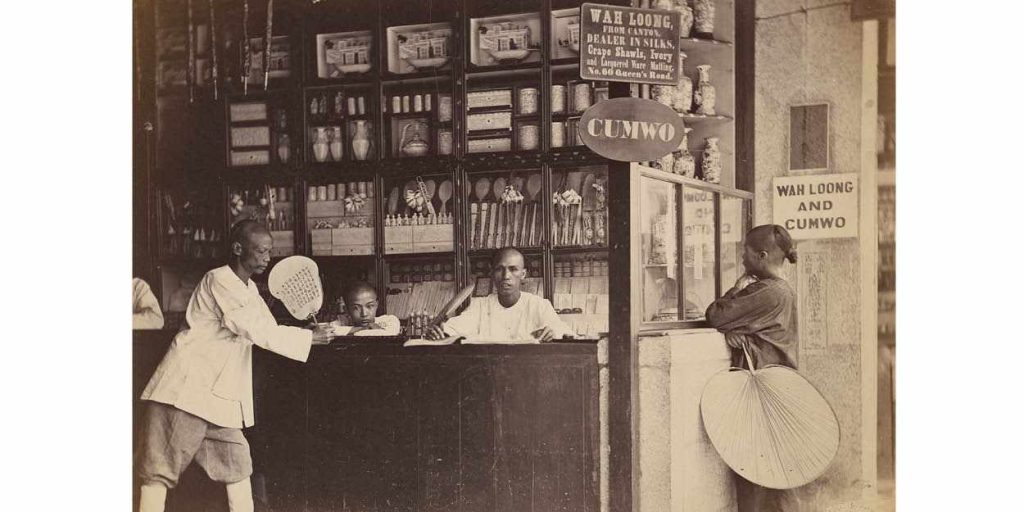

Photographs taken in these complex contact zones often reflect a layered, hybrid culture. In John Thomson’s Curio Shop, a shopkeeper holds a Chinese fan toward the camera that is inscribed with a 16th-century poem, Longtan Night Sitting by Wang Yangming, that evokes a landscape far from the bustling streets of the city. Prominently placed in Thomson’s photograph, this historic poem about trying to find solace in the midst of political conflict, would have been easily recognizable to literate Chinese viewers but enigmatic to foreign viewers.

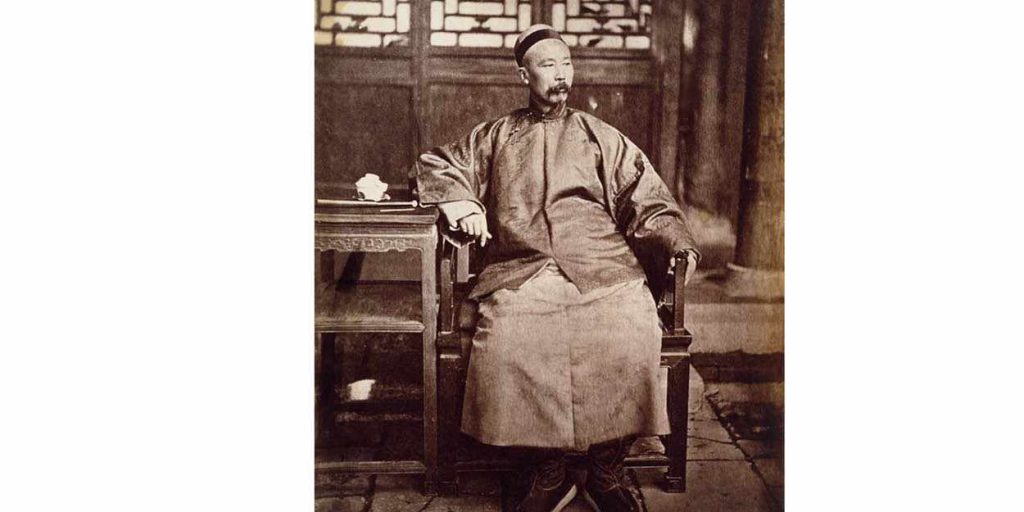

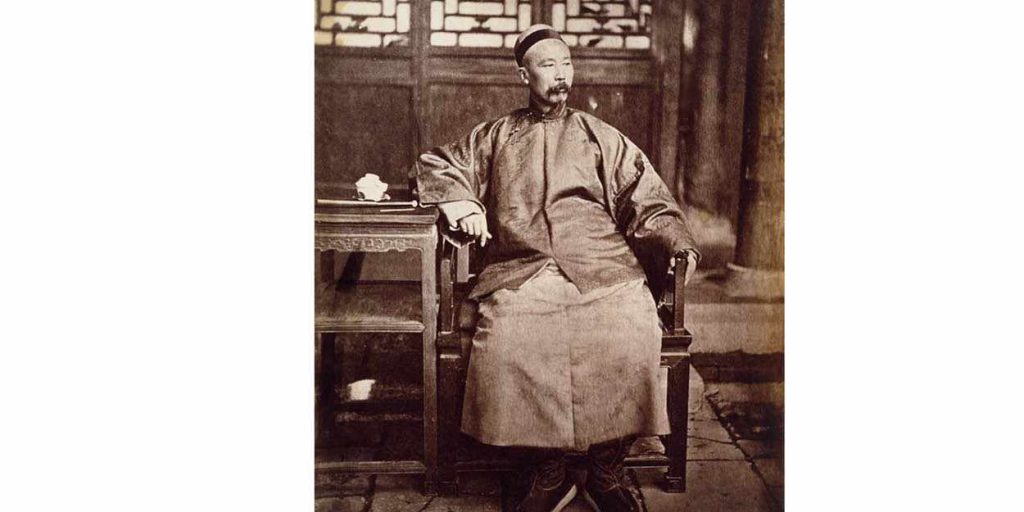

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Chinese sitters harnessed photography as a new medium for self-fashioning. Photography was incorporated into elite social gatherings, rituals, diplomacy, and painting practices. Chinese photographers and sitters created new possibilities for presenting themselves as they wished to be seen by blending traditional modes of representation with the immediacy and reproducibility of photography.

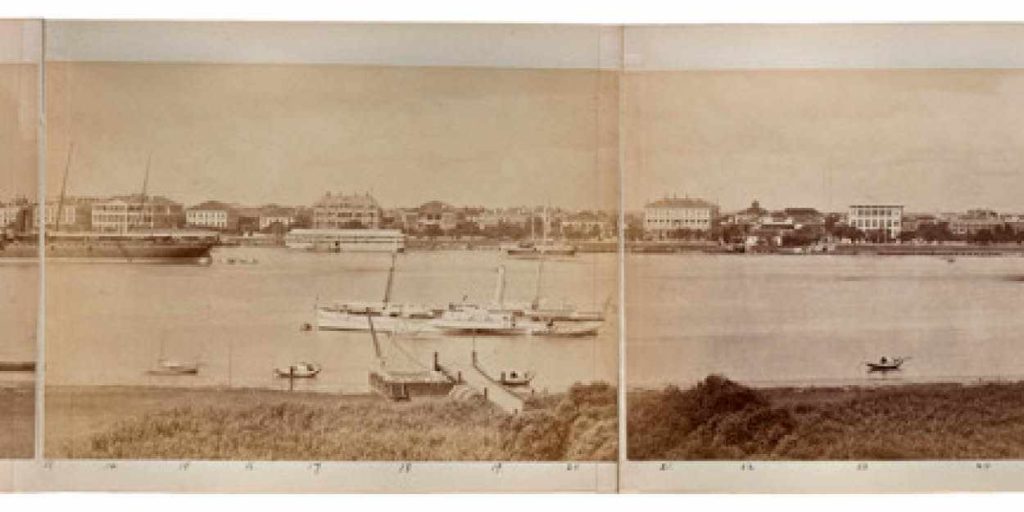

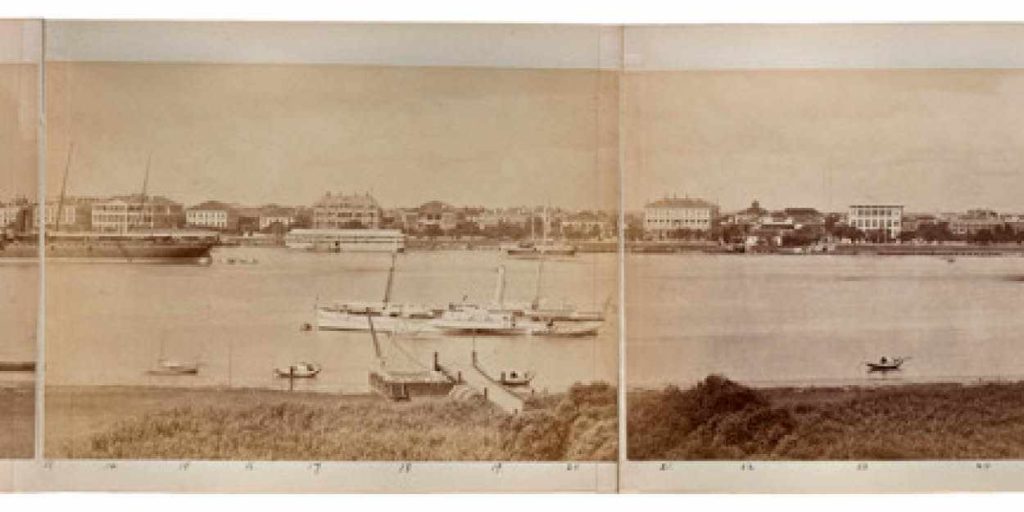

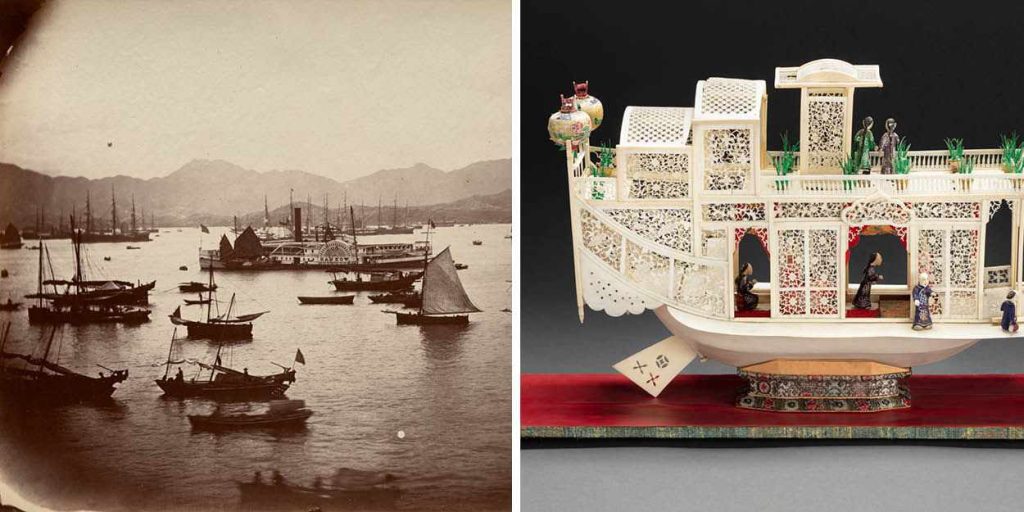

Chinese photographers also captured the thriving commerce along the waterfront in Shanghai in works like this 13-plate panorama produced by Kung Tai studio. Creating photographic panoramas was a complex process involving multiple images taken from a high vantage point. After each shot, the photographer carefully adjusted the camera, later combining the individual prints. The collector of this image added annotations about recent changes to the waterfront, reflecting his intimate knowledge of the rapidly evolving architectural and commercial landscape.

Camera as Narrator

Most of the works in this exhibition were originally part of albums, which offered viewers an intimate encounter with faraway places and people. Tourists often collected and arranged photographs into their own personal travelogs. Professional photography studios also compiled albums, selecting and sequencing images to sell specific narratives. The narratives of China and its people presented in many of these albums are highly subjective and were driven by market appeal.

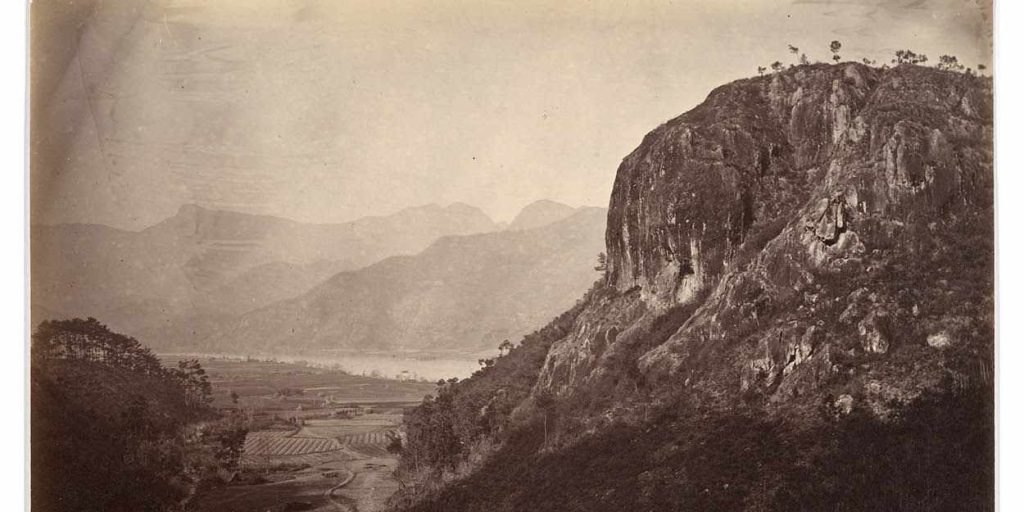

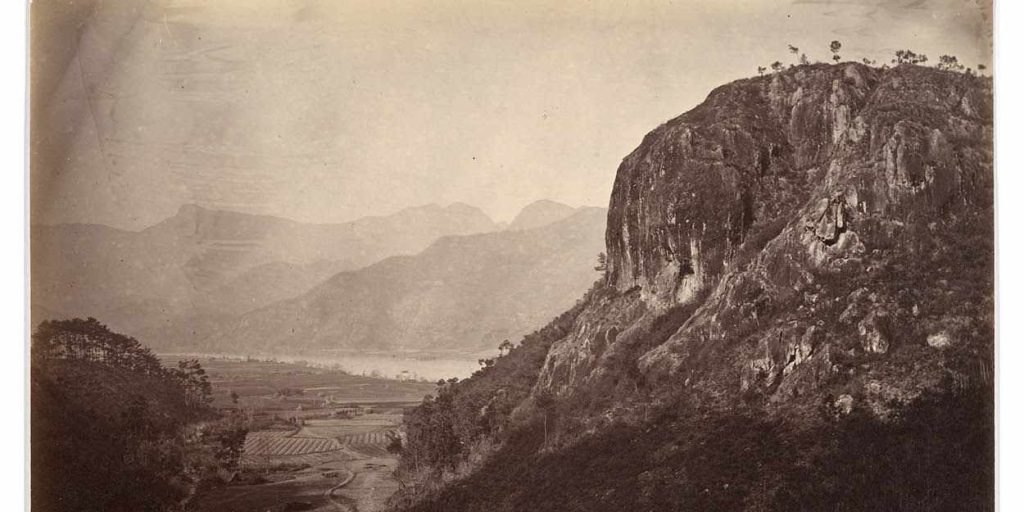

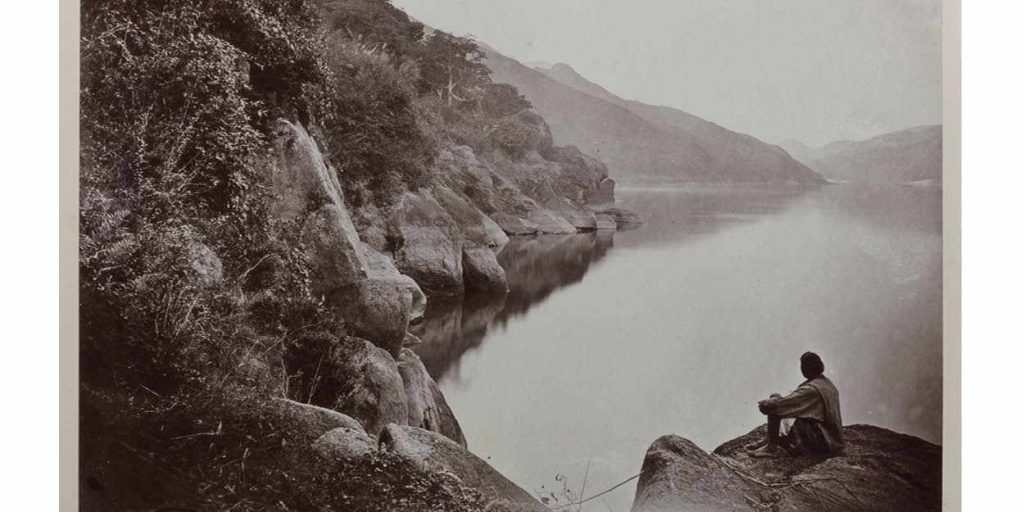

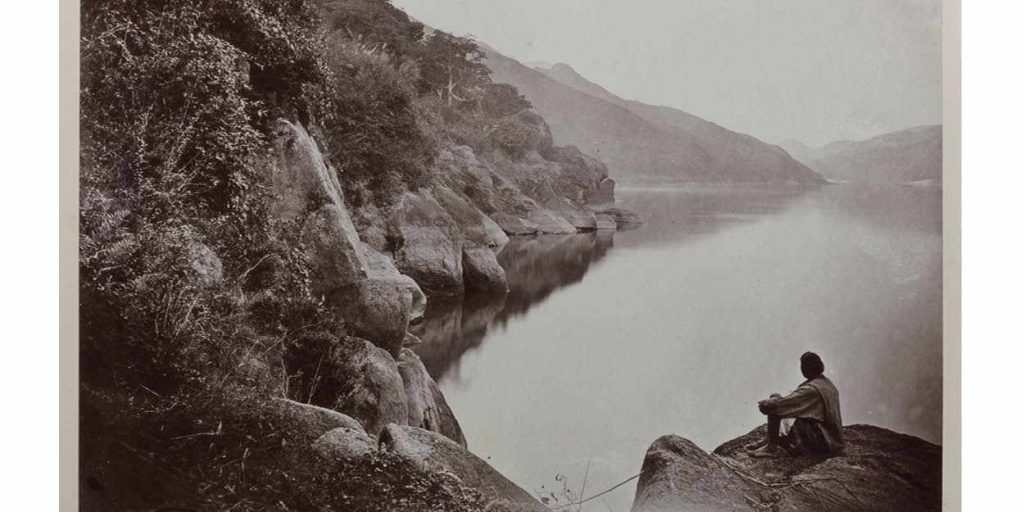

Lai Afong was a pioneering photographer who operated one of the longest-running studios in China. He was the first to compile an album dedicated to Fuzhou, a treaty port renowned for its natural beauty. Lai’s album portrays a meandering, picturesque excursion from the foreign settlements on the coast to the mountainous inland source of the tea trade.

Inspired by Lai’s landscapes, Scottish-born photographer John Thomson ventured from his Hong Kong studio to photograph Fuzhou. Thomson marketed Foochow and the River Min as a luxury souvenir album to Fuzhou’s foreign residents. Of the original 46 copies of the album, only 10 survive, 2 of which are in PEM’s collection.

Stories told through PEM’s Collection

The works in Power and Perspective are drawn primarily from PEM’s rare and singular holdings of photography, Chinese art, and Asian export art, and are supplemented by select loans from public and private collections in the United States and Europe. Approximately half the photographs included in the exhibition and accompanying catalogue have never before been published or displayed. PEM’s roots date to the 1799 founding of the East India Marine Society, an organization of captains and supercargoes who had sailed beyond either the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn and were charged with bringing back a “cabinet of natural and artificial curiosities” for the educational benefit of their peers in Salem, Massachusetts.

The rich, interconnected collections and archives at PEM provide a unique resource for the study of early photography in China. Many merchants returned to Massachusetts from China bringing photographs of their colonial encounters as well as tea, porcelain, ivory, and silks. The exchange and movement of these objects around the world connected societies and helped create a complex global economy that continues to shape our experience today.PEM’s 19th-century Chinese photography collection includes large bodies of work by well-known Western professional photographers, such as Felice Beato, Thomas Child, Louis Legrand, Milton Miller, William Saunders, and John Thomson, and includes rare albums attributed to amateur photographers. Works by Chinese studios such as Lai Afong, Tung Hing, Kung Tai, Ying Cheong, Chow-Kwa, and Pun Lun form a smaller portion of the collection, demonstrating how foreign clientele patronized Chinese and Western studios alike.

Contemporary Perspectives

The technology of photography has changed dramatically since it first arrived in China in 1844. Cameras have become smaller and faster, and an abundance of images makes it seem as though the world is at our fingertips. Yet, digital barriers and gaps in communication limit our perspective.

During a three-month-long virtual collaboration, PEM worked with emerging contemporary photographers from underrepresented groups in China to interrogate the historic photographs in this exhibition. The works they generated offer personal insights into China today. From stories about the land to explorations of gender and the body, their cameras serve as mediums for self-reflection and free expression. Through their words and images, we see that China today—just as it was in the 19th century—is a dynamic place with a multitude of viewpoints.

ABOUT THE PEABODY ESSEX MUSEUM

Over the last 20 years, the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) has distinguished itself as one of the fastest-growing art museums in North America. Founded in 1799, it is also the country’s oldest continuously operating museum. At its heart is a mission to enrich and transform people’s lives by broadening their perspectives, attitudes, and knowledge of themselves and the wider world. PEM celebrates outstanding artistic and cultural creativity through exhibitions, programming, and special events that emphasize cross-cultural connections, integrate past and present, and underscore the vital importance of creative expression. The museum’s collection is among the finest of its kind boasting superlative works from around the globe and across time — including American art and architecture, Asian export art, photography, maritime art and history, Native American, Oceanic, and African art, as well as one of the nation’s most important museum-based collections of rare books and manuscripts. PEM’s campus offers a varied and unique visitor experience with hands-on creativity zones, interactive opportunities, and performance spaces. Twenty-two noted historic structures grace PEM’s campus, including Yin Yu Tang, a 200-year-old Chinese house that is the only example of Chinese domestic architecture on display in the United States. HOURS: Open Thursday, Saturday–Monday, 10 am–5 pm; Friday 10 am–7 pm. ADMISSION: Adults $20; seniors $18; students $12. Members, youth 16 and under, and residents of Salem enjoy free general admission. INFO: Call 866-745-1876 or visit pem.org.

What is Creative Collective?

Creative Collective is a group of economic development strategists, small business supporters, activation specialists, and believers in the importance of the creative workforce. We foster growth, sustainability, and scalability for small businesses, creative thinkers, organizations, entrepreneurs, and innovators.

Learn more and join Creative Collective at www.creativecollectivema.com/join